Vermeer’s Women

His most famous model, the adolescent girl with the oriental headdress, or, if you prefer, Girl With a Pearl Earring, is either one of his oldest daughters, Maria or Elizabeth. I believe she is the same person in The Girl Writing a Letter.

To say The Girl Writing a Letter has alopecia is a bit rich but she has a high forehead even in the style of the day, and perhaps judged more favorably for it. The girl with the pearl earring indicates no particular hairstyle. One can assume she has hair under there. The painting of the letter writer- I see this portrait as an advertisement for a marriage-aged daughter in an overcrowded house as much as a demonstration of skill for potential commissions or covering a favorite subject then in vogue: Female letter writers (You got me). Otherwise, I’m not sure what the point of the painting is. I’m certain the man loved his daughters and was happy to bestow a certain immortality by essaying them in paint; that, though, is the kind of romance I bristle at when on the one hand you have a professionally trained painter trying to make his substantial financial nut through his talent, but at the same time finding time to pose his daughters for posterity. It’s not impossible to accept such sentiment, but if Vermeer painted so few pictures and some are for the family album then the argument that he spent most of his energy as a copyist gets stronger. I suspect with this item he was killing two birds with one stone. He was employing his readymade model daughter in pursuing the trends of the market, and bringing awareness to the locally affluent that this creature is quite a catch.

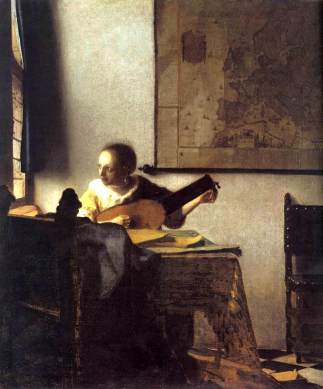

Woman With a Lute is the same girl as the letter writer. Why she’s tagged as a woman is beyond me- she looks about fourteen- the girl with the high forehead again (and the ubiquitous pearl earring.) At this point, that earring is starting to look like nothing more than a device, a prop to give the shadowed side of the face a spot of light. It’s a good trick, and frankly no one was assessing Vermeer’s technical schemes in whole, save himself. So what if that damn earring suggests there’s only one earring in a whole house full of females? A painter can fetishize like no one else when they get to liking a gimmick.

I also wonder about the ermine trimmed yellow jacket that is as popular for Vermeer as his earring. Is this the best piece of glad rag they had? The repetition of elements in the oeuvre suggests there may have been very little to spruce up the pictures and this, too, may account for the lack of interest from the buying public. I have to wonder that if one painting of a woman in yellow and pearl isn’t selling, why keep at it?

Of all the claims I’ve made in this series, the following is the most conjectural: I stated before that Pieter Claesz Van Ruijven was not Vermeer’s patron exactly but his financial backer- there is a difference. Van Ruijven sunk money into Vermeer, and the camera obscura, for the express purpose of copying best sellers for the foreign market. The attempt to get Vermeer a name for himself was secondary to that- at the same time, Van Ruijven had some say over what Vermeer was trying to market. To this end, Van Ruijven, who I truly believe owned Vermeer’s output past and future, insisted Vermeer keep painting pictures of these precious young women. I can’t say what the age of consent was in Holland at the time but I’m sure it was younger than 16 which is what it is today. For us, Van Ruijven then seems like a lecherous old bastard, which is how he was portrayed in the film, Girl With A Pearl Earring, by Tom Wilkinson (who was much older than Van Ruijven at his death, aged forty nine.) I wouldn’t tar and feather Van Ruijven even if he may be playing a subtle game with his employee. Men like female beauty, and real time and place beauty whenever possible. But paintings of unrequited crushes, let’s say, can take hold of the male gaze. By the looks of things in Dutch culture of the time, women weren’t tasked with showing much in the way of smarmy flesh. What they could do is look placid, gentle, entertaining in a discreet fashion, clearly tied to the domestic side of life, and of course, pretty, in a way that would flatter a man. What a Van Ruijven did with all this delicate implication would be too much information, but all the hyper-feminine gentility in the Van Ruijven collection of Vermeers is there, I believe, largely at the behest of the man keeping Vermeer afloat. And running deep underneath this claim is something a little more sinister- the idea that Vermeer was trading on his daughter’s appeal to provide some balance to an inequitable financial arrangement. Like I said- the most conjectural claim, yet…

Girl writing a letter, if I can be so in the present, first thing I think is she is got her hair in rollers, and second … yikes! Run away!

LikeLike